In 2021, Experian analysed fraud patterns at a single UK energy company (unnamed - Experian anonymises its clients) and found 1,500 directors linked to over £100 million of live debt - all created through fake change of tenancy claims. That was one supplier, five years ago. The problem was serious enough that in 2025, Ofgem approved the first standardised evidence framework (REC Schedule 33) specifically to address it.

The directors weren’t moving premises. They were closing companies, reopening under new names, and misrepresenting the periods they occupied commercial properties. The result: energy suppliers left holding contracts for meter points with no paying customer, energy already hedged with no one to bill, and debt that couldn’t be recovered.

This is Change of Tenancy fraud - and it’s a known, quantified, and growing problem that energy suppliers, brokers, and regulators are only now starting to properly address.

TL;DR: Key Takeaways

- The scale: In 2021, Experian identified 1,500 directors linked to £100m+ in energy debt via CoT fraud at a single supplier. That was one company, five years ago. Industry-wide, the figure today is substantially higher.

- How it works: Businesses fake a legal change (close company, reopen under new name, convert sole trader to Ltd) to trigger a change of tenancy event and walk away from fixed-term contracts.

- Broker involvement: Documented cases of brokers illegally changing tenancy names on thousands of accounts, collecting commission from new suppliers while old suppliers eat the debt.

- Supplier cost: BSC settlement is agnostic to why a customer leaves. Suppliers face full imbalance charges, hedging losses, and bad debt write-offs with no regulatory compensation.

- The regulatory gap: No Ofgem enforcement action has ever specifically prosecuted fraudulent CoT. That changes when direct TPI regulation arrives in 2027-2028.

What is Change of Tenancy fraud?

The Change of Tenancy (CoT) process - also called Change of Occupier (CoO) in regulatory language - is a legitimate mechanism. When a business genuinely moves premises or undergoes a real legal change, the energy supply at that meter point transfers to the new occupier. The incoming business starts a new contract or goes onto deemed rates. The outgoing business’s contract at that site ends.

CoT fraud exploits this process. Instead of genuinely changing premises, a business fabricates a legal change to trigger a CoT event and escape an existing contract - typically to avoid termination fees or outstanding debt.

The common patterns

Experian’s B2B fraud analysis (opens in new tab) identified specific tactics:

- Serial company dissolution and recreation. Directors close a limited company that owes energy debt, then incorporate a new company at the same address. The new entity claims a CoT event - technically a new legal person is occupying the premises - and the old debt is left with the dissolved company.

- Misrepresenting occupancy periods. Businesses manipulate the dates they claim to have occupied or vacated premises, creating gaps that leave suppliers unable to bill anyone for energy consumed during those periods.

- Sole trader to limited company conversion. A sole trader converts to a limited company (new Companies House number). Under industry rules, this counts as a CoT event because the “consumer at the premises” has changed - even though the actual person and business operation haven’t moved.

The last one is particularly difficult for suppliers to challenge. A genuine sole-trader-to-Ltd conversion is a legitimate business event that triggers a real CoT. The same mechanism used fraudulently is almost impossible to distinguish from the outside.

The broker connection

Most CoT fraud is driven by businesses acting alone - directors who’ve figured out (or been told) that closing and reopening a company can void an energy contract. But there are documented cases of brokers actively facilitating the process, and even a small number of bad actors doing this at scale creates significant damage.

Champion Energy (opens in new tab) describes schemes where a broker helped customers illegally change tenancy names on thousands of gas and electricity accounts. The original suppliers were left with outstanding debts while the broker collected commission from new suppliers by switching the “new tenants” onto fresh contracts.

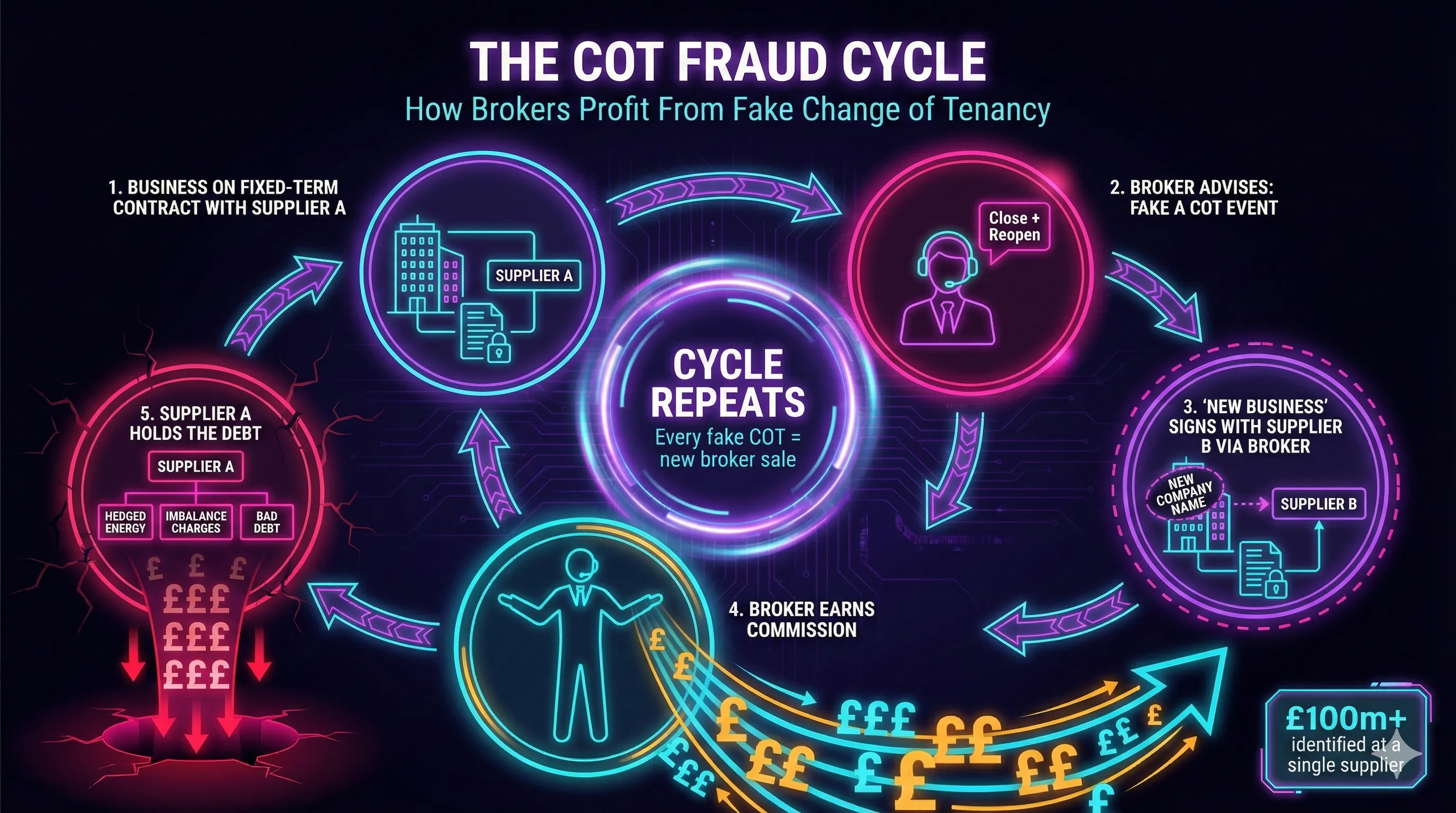

This isn’t representative of the whole broker market. But the financial incentive that makes it possible is worth understanding, because it’s exactly the kind of behaviour that incoming TPI regulation is designed to catch:

- Business is on a fixed-term contract with Supplier A.

- Broker advises business to fake a CoT event (e.g. close company, reopen).

- “New business” signs a contract with Supplier B through the broker.

- Broker earns commission on the new contract.

- Supplier A is left with unpaid debt and hedged energy for a customer that no longer exists.

Every fraudulent CoT is a new “sale” for the broker. The worse the original contract, the more motivated the customer. The more motivated the customer, the easier the broker’s pitch. It’s a rare but lucrative pattern - and it’s precisely why the government decided self-regulation wasn’t enough.

These cases exist within a broker ecosystem where only 52 of 2,700+ brokers signed the voluntary TPI Code, where complaints surged 112% in 2024, and where undisclosed commissions inflated bills by up to 31%. CoT fraud facilitated by brokers may be uncommon, but it thrives in the same regulatory vacuum that enables mis-selling - which is exactly why incoming regulation matters.

What it costs suppliers when customers disappear

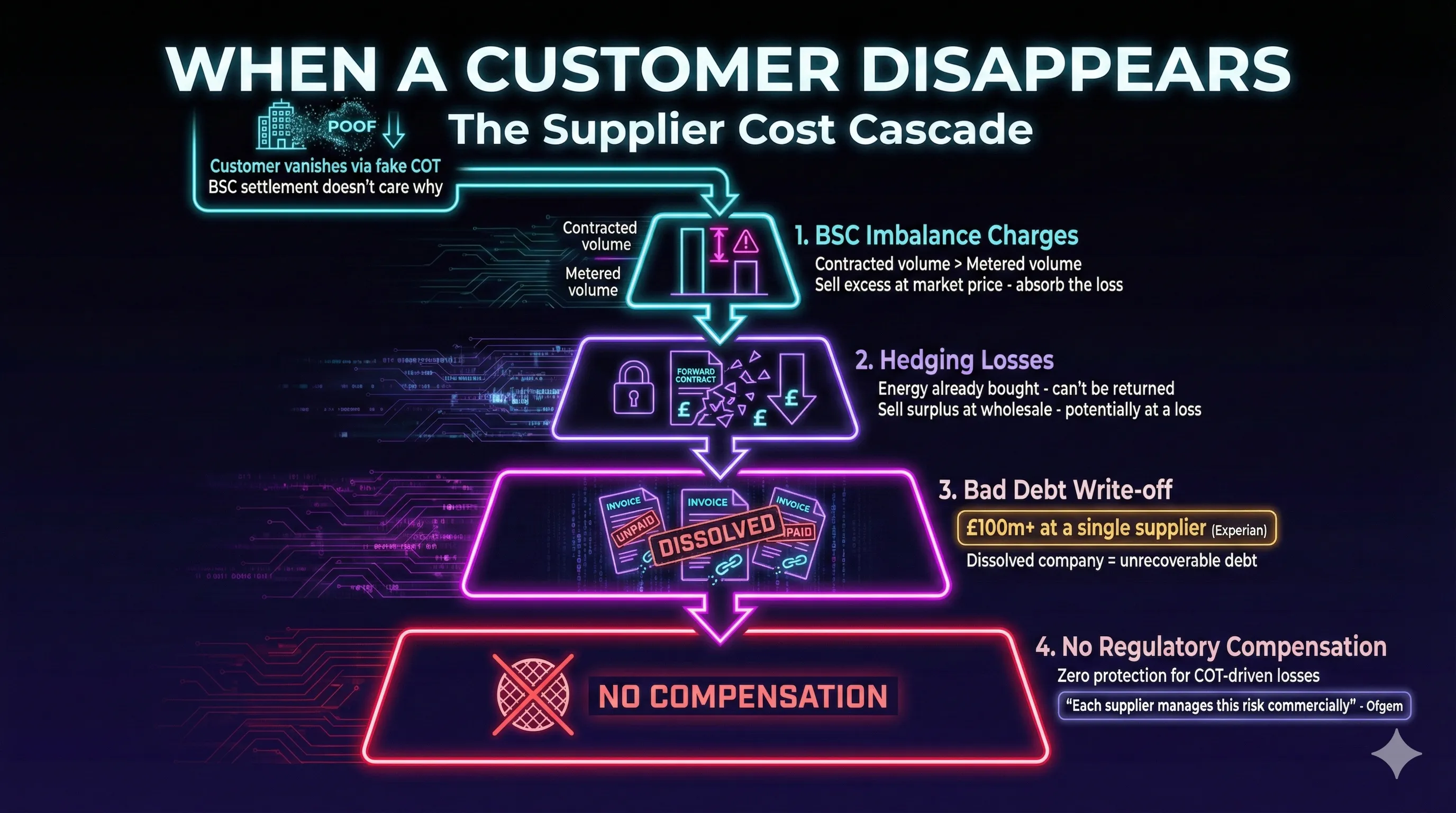

When a customer exits via CoT - genuine or fraudulent - the energy supplier doesn’t just lose a customer. They face a cascade of financial exposure that no regulatory mechanism compensates for.

How settlement works

Under the Balancing and Settlement Code (BSC) (opens in new tab), Elexon compares each supplier’s contracted volume (energy purchased in advance) against their metered volume (energy their customers actually consumed) for every half-hour period.

Any mismatch is an imbalance. If the supplier has over-contracted - because they hedged energy for a customer who suddenly doesn’t exist - they must sell the excess at the prevailing Energy Imbalance Price. If the market has moved against them, that’s a loss they absorb entirely.

The BSC is agnostic to why a supplier’s portfolio changes (opens in new tab). Competitive loss, genuine CoT, insolvency, fraud - the settlement system treats them all the same. There are no special imbalance relaxations for CoT-driven volume loss.

The hedging problem

Non-domestic energy suppliers don’t buy energy in real time. They hedge - purchasing energy months or years in advance based on their projected customer portfolio. A customer on a 3-year fixed contract represents a known volume of energy that the supplier has already procured.

When that customer disappears mid-contract:

- The energy is already purchased and can’t be “returned”.

- The supplier must sell the surplus into the wholesale market - potentially at a significant loss if prices have dropped since the hedge was placed.

- There are no REC or BSC provisions that compensate suppliers for hedging losses from CoT events.

- Ofgem’s deemed contracts guidance (opens in new tab) explicitly states it “does not prescribe pricing methodologies or hedging strategies” - each supplier manages this risk commercially.

This is precisely why termination fees exist in non-domestic contracts. They’re designed to cover the supplier’s “direct economic loss” from unwinding hedged positions when a customer breaks a contract early. For domestic customers, the law caps these fees at actual economic loss. For non-domestic customers, there is no equivalent cap.

When a business uses fraudulent CoT to dodge those fees, the supplier eats the full loss.

The regulatory tension: fraud prevention vs fair treatment

Here’s the problem regulators face. Suppliers have a legitimate interest in verifying CoT claims - the fraud is real and the losses are substantial. But heavy-handed verification harms genuine businesses trying to move premises.

The Maxen Power case

In 2024-2025, Ofgem took enforcement action against Maxen Power Supply (opens in new tab), resulting in a £1.65 million payment for customer service failures. Among the findings:

- Maxen “put unreasonable requirements on customers to evidence a change of tenancy by asking for a large number of documents”.

- Delays in gathering these documents risked customers being “locked into a more expensive deemed rate tariff”.

- New occupiers were threatened with disconnection unless they paid the previous tenant’s debt - despite having provided evidence they were a different legal entity.

Ofgem’s Standards of Conduct guidance (opens in new tab) (SLC 0A) explicitly cites this pattern - protracted CoT processes combined with threats over predecessor debt - as an example of conduct that may breach licence conditions. The guidance now applies to all non-domestic customers, not just microbusinesses, following the 2024 Non-Domestic Market Review.

So suppliers face a double bind: do too little verification and you eat fraudulent losses. Do too much and you face regulatory action for mistreating genuine customers.

The REC’s attempt at balance: Schedule 33

REC change R0155 (opens in new tab) - approved by Ofgem in February 2025 and implemented on 27 June 2025 - introduced Schedule 33, the first standardised framework for non-domestic Change of Occupier. It tries to balance both sides:

For suppliers (fraud prevention):

- A non-exhaustive list of acceptable evidence documents (leases, Land Registry, business rates, solicitor letters, Companies House filings).

- Both gaining and losing suppliers must retain CoT evidence for at least one year (REC Schedule 23), creating an audit trail for disputes.

For customers (fair treatment):

- Suppliers must review evidence within 10 working days.

- If additional evidence is needed, suppliers must explain specifically what’s missing and why.

- An additional 10 working days from receipt of extra evidence for final decision.

- Suppliers cannot demand documents “a reasonable occupier could not be expected to have”.

Before R0155, there were no standardised evidence requirements and no SLAs. Suppliers could (and did) demand excessive documentation while customers languished on expensive deemed rates.

How suppliers detect fraud today

Beyond the REC framework, detection relies on:

Credit and data analytics. Experian’s work for energy companies uses director-linkage analytics to spot patterns - the same director appearing across multiple dissolved companies, serial non-payment, and occupancy periods that don’t match tenancy records. This is how the 1,500-director / £100m figure was identified.

Internal policies. Suppliers maintain their own fraud controls, but these vary wildly in sophistication. Larger suppliers have dedicated fraud teams. Smaller ones may have limited capability to cross-reference director histories.

“Legal changes at same premises” scrutiny. Sole-trader-to-Ltd conversions and partnership changes at the same address receive more scrutiny because they’re the highest-risk CoT type - the business hasn’t physically moved, only the legal entity has changed.

The evidence retention requirement. Under REC Schedule 23, both gaining and losing suppliers must keep CoT evidence for at least one year when a switch is flagged as Change of Occupier. This enables post-hoc audit but relies on someone actually checking.

The regulatory gap

Despite the scale of the problem, there is a significant enforcement gap.

No Ofgem enforcement action has ever specifically prosecuted a business customer or broker for fraudulent CoT. Published enforcement focuses on supplier behaviour (mis-selling, unfair terms, poor complaints handling) rather than customer-initiated fraud.

No published court or tribunal decisions centre specifically on fraudulent CoT claims in business energy as the primary issue. CoT abuse tends to appear as part of wider fraud patterns - like the BES Utilities case (opens in new tab) where the owner was jailed for fraud related to energy contracts - rather than as standalone CoT fraud.

The voluntary TPI Code hasn’t addressed it. With only 2% of brokers signed up, the Code has no meaningful reach into the broker practices that enable CoT fraud.

The result is that fraudulent CoT is recognised and acted on operationally by individual suppliers, but hasn’t crystallised into a body of enforcement or case-law. Suppliers manage it as a commercial risk, not a regulatory one.

What’s coming: TPI regulation and the closing window

The window for consequence-free CoT fraud is narrowing.

Following Ofgem’s recommendation in the Non-Domestic Market Review (opens in new tab), the government confirmed in October 2025 (opens in new tab) that Ofgem will become the direct regulator of TPIs for the first time. The framework:

- “Hybrid” general authorisation model - TPIs arranging energy procurement will need authorisation from Ofgem.

- Ofgem powers: Set rules, monitor conduct, investigate, order redress, levy fines, and exclude non-compliant TPIs from the market.

- 12-18 month “sunrise period” for existing TPIs to register and comply.

- Expected timeline: 2027-2028 for mandatory enforcement.

Once this framework is live, advising clients to fabricate CoT claims will sit squarely within Ofgem’s enforcement remit. For the first time, regulators will be able to act directly against the brokers driving the fraud - not just the suppliers caught in the middle.

Ofgem has already signalled its intent by rejecting REC change proposals R0137/R0137A (opens in new tab) that would have created a parallel TPI accreditation regime within the REC - explicitly on the basis that direct statutory regulation is coming and they don’t want overlapping frameworks.

The regulatory direction is clear. The question is whether the 12-18 month sunrise period becomes a last-chance window for bad actors, or whether the industry uses it to clean house before Ofgem starts asking questions.

What this means for businesses

If you’re a business considering a CoT claim to exit a contract, here’s the reality:

Genuine CoT is your right. If you’re actually moving premises, changing legal entity for real business reasons, or undergoing a genuine business sale - the CoT process protects you. Suppliers must process your claim within 10 working days under REC Schedule 33. You are not liable for the previous tenant’s debt. And you cannot be blocked from switching away from deemed rates.

Fake CoT is fraud. If someone - a broker, a consultant, a friend in the pub - suggests closing your company and reopening under a new name just to escape an energy contract, that’s not a clever workaround. It’s fraud. Directors who do this are being tracked through credit analytics. The £100m in identified debt at a single supplier shows the scale at which this is now being monitored.

The contract still matters. Even a genuine CoT doesn’t automatically waive termination fees. Most non-domestic contracts treat early departure - for any reason - as early termination. Some suppliers waive fees if you transfer to their supply at new premises. But that’s commercial goodwill, not a right.

If you’re stuck in a bad contract and feel trapped, there are legitimate routes. Complain to the Energy Ombudsman. Check whether the contract was mis-sold. Review the T&Cs for unfair clauses. Don’t let someone sell you a CoT claim as a shortcut.

The bottom line

Change of Tenancy fraud is a real, quantified problem costing the UK energy market hundreds of millions of pounds. It’s enabled by a broker market that’s been unregulated for decades, facilitated by a CoT process that until June 2025 had no standardised evidence requirements, and tolerated because enforcement has focused on supplier behaviour rather than the fraud itself.

The regulatory pieces are now falling into place - REC Schedule 33, expanded Standards of Conduct, and direct TPI regulation. But between now and 2028, the system relies largely on individual suppliers’ ability to detect and challenge fraudulent claims.

For legitimate businesses, the new rules should make genuine CoT faster and fairer. For the 1,500+ directors that Experian identified running serial CoT fraud at just one supplier - the clock is ticking.

This article draws on Experian’s B2B Commercial Fraud Insights paper, Ofgem’s Non-Domestic Market Review decision, REC change proposal R0155, Ofgem’s enforcement action against Maxen Power Supply, and the government’s October 2025 response on TPI regulation. All claims are sourced from regulatory documents, enforcement decisions, or industry publications.